Introducing Stowa Adds Six New Models to the Flieger Classic Collection

Welcome to the hub of the horoloy

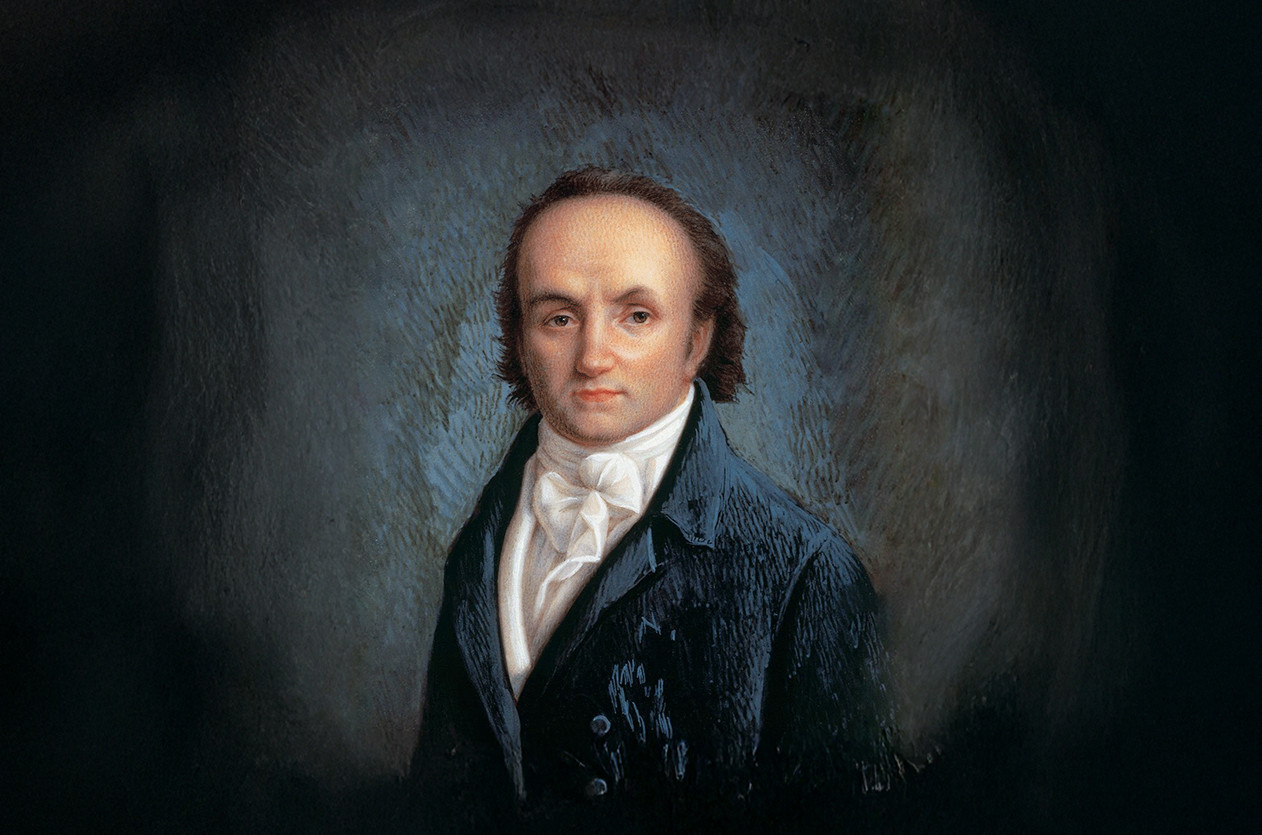

A journey through the early years of Breguet and his revolutionary innovations

When we talk about Breguet, one of the first innovations that comes to mind is the tourbillon, a groundbreaking invention designed to counteract the effects of gravity on a watch's accuracy. However, this invention, while iconic, is not the only mark Abraham-Louis Breguet left on the world of horology. Breguet's contributions to watchmaking are vast, revolutionary, and still resonate in the industry today.

|  |

Abraham-Louis Breguet was born in 1747 in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and moved to Paris in his teens to train as a watchmaker. It wasn’t long before he opened his own workshop in 1775 on the Quai de l'Horloge, located on Île de la Cité island. With his innovative designs and talent, Breguet quickly gained attention, especially after being introduced to the French court by Abbé Marie, who was a mentor to the young watchmaker. The Queen of France Marie-Antoinette would go on to become one of his most ardent admirers, ordering several pieces that set the stage for Breguet’s reputation.

In 1780, Abraham-Louis Breguet unveiled the Perpétuelle, the first automatic watch, featuring a groundbreaking self-winding mechanism that earned him recognition not only in France but throughout Europe. This innovation addressed the longstanding issue of manually winding watches. The term Perpétuelle refers to Breguet’s self-winding watches, a major milestone in his career, particularly at a time when others had struggled to develop a functional solution. Breguet’s breakthrough came with the oscillating platinum-weight mechanism, which proved both effective and reliable. His first Perpétuelle, sold to the Duc d’Orléans in 1780, marked the beginning of his fame, with his self-winding watches becoming highly coveted in the courts of Versailles and beyond.

The Perpétuelle was both technically and aesthetically revolutionary, a timepiece fit for royalty, and it remains a testament to Breguet's extraordinary inventive brilliance. The earliest surviving example, the Breguet Perpétuelle repeating watch No. 1/8/82, was completed in 1782. This model showcased the innovative oscillating platinum weight that allowed the watch to wind itself automatically.

Around the same time, Breguet began experimenting with different watches. In 1783, he created the first repeating watch to use a gong-spring rather than the traditional bell. His continuous push for precision and perfection also led him to develop the Breguet balance-spring, which improved the accuracy of watches and reduced wear on the balance wheel axis. This invention became another key component of Breguet’s enduring legacy.

Around the same time, Breguet began experimenting with different watches. In 1783, he created the first repeating watch to use a gong-spring rather than the traditional bell. His continuous push for precision and perfection also led him to develop the Breguet balance-spring, which improved the accuracy of watches and reduced wear on the balance wheel axis. This invention became another key component of Breguet’s enduring legacy.

However, the French Revolution would dramatically change Breguet’s life, forcing him to leave Paris in 1793. He spent several years in his native Switzerland, but his influence in horology didn’t wane. He continued to develop new ideas, and upon his return to Paris in 1795, he began to work on projects that would later secure his place in history.

Two years later, Breguet introduced his “souscription” or subscription watches, simple yet reliable timepieces that gained immense popularity for their affordability and quality. One notable example is a relatively large 61mm model with a single hand and an enamel dial. Breguet marketed these watches through an advertising brochure, selling them on a subscription basis. Customers were required to pay a quarter of the price upfront when placing an order. These watches were both dependable and reasonably priced, resulting in significant success and the attraction of a broad new customer base.

Two years later, Breguet introduced his “souscription” or subscription watches, simple yet reliable timepieces that gained immense popularity for their affordability and quality. One notable example is a relatively large 61mm model with a single hand and an enamel dial. Breguet marketed these watches through an advertising brochure, selling them on a subscription basis. Customers were required to pay a quarter of the price upfront when placing an order. These watches were both dependable and reasonably priced, resulting in significant success and the attraction of a broad new customer base.

Breguet’s innovations were not limited to mechanical improvements. In 1799, he unveiled the tact watch, which was designed for the visually impaired, allowing them to "read" the time by touch. The watch featured a pointer that mimicked the position of the hour hand, offering an ingenious solution for those unable to see the dial.

Breguet’s innovations were not limited to mechanical improvements. In 1799, he unveiled the tact watch, which was designed for the visually impaired, allowing them to "read" the time by touch. The watch featured a pointer that mimicked the position of the hour hand, offering an ingenious solution for those unable to see the dial.

One of Breguet's most renowned clients was Queen Caroline of Naples, who between 1808 and 1814 acquired a total of thirty-four clocks and watches, securing her position as one of Breguet's most prestigious customers. The younger sister of Napoleon, she reigned alongside her husband, King Joachim Murat, from 1808 to 1815. During this time, her special relationship with Breguet led to the creation of the first wristwatch ever designed for this purpose. Commissioned in 1810, paid for in 1811, and delivered in 1812, this groundbreaking timepiece was an ultra-thin repeating watch with an oblong shape, featuring a thermometer and mounted on a wristlet made from hair intertwined with gold thread. This design is what we know today as Reine de Naples.

In the summer of 1813, when the European crisis had reached its peak and the firm had lost many of its top clients, Queen Caroline came to Breguet's aid. She purchased twelve more watches, eight repeating and four simple models, providing a crucial financial boost to the business at a time when it was most needed.

In 1815, Breguet received one of his highest honors when he was appointed Chronometer-Maker to the French Royal Navy. The precision of his marine chronometers played a crucial role in navigation, enabling sailors to calculate longitude at sea with far greater accuracy. This appointment solidified Breguet’s status as one of the most respected watchmakers in the world.

In 1815, Breguet received one of his highest honors when he was appointed Chronometer-Maker to the French Royal Navy. The precision of his marine chronometers played a crucial role in navigation, enabling sailors to calculate longitude at sea with far greater accuracy. This appointment solidified Breguet’s status as one of the most respected watchmakers in the world.

Breguet’s death in 1823 marked the end of an era, but his influence did not end there. His son, Antoine-Louis Breguet, took over the business and continued his father’s work, preserving and advancing the incredible legacy of innovation. Abraham-Louis Breguet’s name is forever linked to the finest craftsmanship, but his true genius lies in the wide array of innovations he introduced to the world of horology. His legacy is not simply in the complexity of his timepieces, but in his ability to continuously push the boundaries of what was possible, all while making timepieces that were both functional and beautiful. Breguet’s work transformed watchmaking, and his influence still shapes the art of timekeeping today.

Introducing A. Lange & Söhne Unveils The New Zeitwerk Minute Repeater

Editorial What is the reason behind the scarcity of Rolex watches in boutiques?

News Ahmed Seddiqi & Sons Joins Rolex Certified Pre-Owned Programme

Introducing Hanhart Expands Its 417 ES Collection with Panda and Reverse Panda Editions

Introducing H992: A New Independent Brand Rising in Swiss Watchmaking

Editorial U.S. Tariffs and the Dollar Rate, A New Challenge for the Swiss Watch Industry

News Dubai Watch Week 2025 Will Be the Largest Ever with 90 Brands Participating

Technical The Frequency, Why It Matters in Mechanical Watches

Editorial The Secrets of Watch Case Design

Introducing Abu Dhabi Hosts the Launch of Greubel Forsey's 20th Anniversary Nano Foudroyante

Comment Delete Text

This page is available in English only. Please click below to visit Arabic Home page!